The Matador’s Nightmare: How Roberto Duran Turned Brawling Into a Masterclass

In the traditional imagery of a bullfight, the roles are clearly defined. The matador is the technician, the artist. Dressed in shimmering regalia, he moves with grace and precision, admired not just for surviving the bull, but for doing so beautifully. The bull, on the other hand, is driven by instinct. It charges forward with rage, unaware of the game it’s in, praised more for its raw bravery than for any strategy.

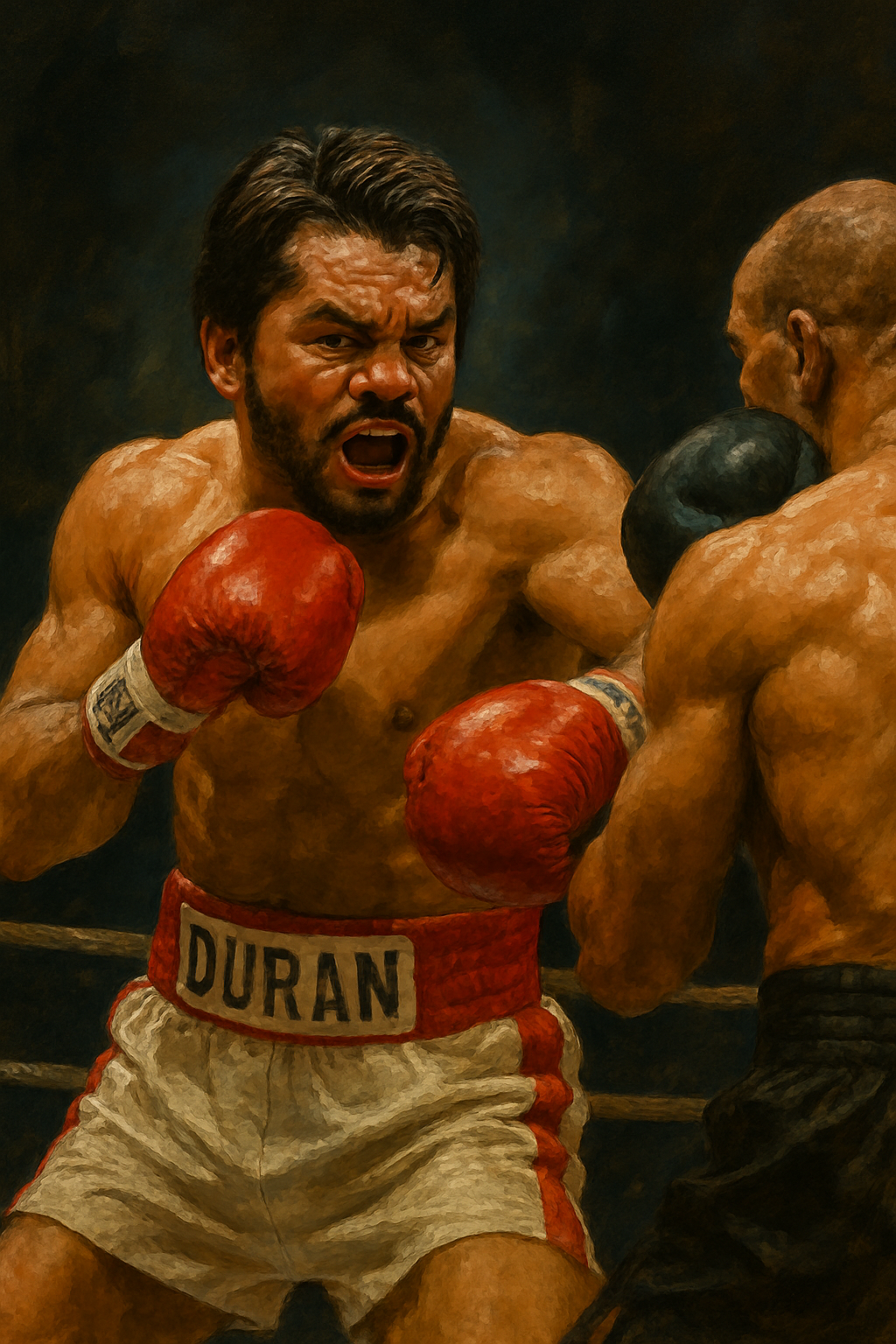

This analogy is often borrowed in boxing circles. In every bull-versus-matador matchup, one fighter is the smooth technician—slick, agile, and elusive—while the other plays the part of the relentless pressure fighter, sometimes dismissed as brutish or basic. But sometimes, the bull isn’t just a beast of instinct. Sometimes, the bull knows how to dance.

No fighter proved that better than Roberto Duran.

The Craft of Chaos

Duran, born in Panama City and raised in poverty, didn’t come into the sport as a polished Olympic darling like his later opponent, “Sugar” Ray Leonard. He wasn’t groomed for greatness by networks or brands. He earned his reputation in the trenches of the ring, fight after fight, forging a style that many mischaracterized as savage. But behind the grit was an almost surgical level of precision.

While the boxing world often talks up defensive wizards—fighters like Floyd Mayweather, Pernell Whitaker, or Willie Pep—it rarely reserves the same praise for pressure fighters. Duran challenged that imbalance. He didn’t just come forward; he came forward with purpose, intelligence, and craft.

To say Duran was simply a brawler is like saying Picasso just doodled.

The Night That Changed Everything: Duran vs. Leonard I

June 20, 1980. Montreal. A location poetic in its symbolism—this was the city where Sugar Ray Leonard had achieved Olympic glory just four years prior. Leonard, the media darling, had speed, charm, and the style of a classic matador. He was supposed to outmaneuver Duran, outthink him, and possibly embarrass him with slick footwork and well-timed counters.

The general belief was that Duran, playing the bull, would storm forward and tire himself chasing a ghost. But that night, Duran flipped the script.

From the opening bell, Duran didn’t just attack—he dissected. He used head movement so sharp it looked like choreography, slipped punches at close quarters, and pounded Leonard’s body until the pretty footwork disappeared. Leonard was drawn into a kind of fight he wasn’t used to. He abandoned his matador role and, willingly or not, stepped into the ring Duran built for him.

That wasn’t luck. That was genius.

Fighting in a Phone Booth—But With a Brain

Close-quarters combat is a dangerous place to live in a boxing ring. The margin for error shrinks, the chances of being caught with a fight-ending punch rise, and chaos becomes the norm. Yet Duran made it feel like home.

In the so-called “pocket”—the range where punches are exchanged without much space—Duran thrived. He didn’t just throw punches blindly. He rolled with shots, anticipated counters, and delivered combinations that flowed from instinct sharpened by years of practice. He didn’t come forward like a brute; he flowed forward like water with fists.

He often ducked low, rolled under punches, and came up throwing hooks with venom. His defense, particularly in close, was masterful—not built on avoidance but manipulation. He was hiding in plain sight, slipping shots that should’ve landed flush and making his opponents pay for every miss.

To fight Duran was not just to endure pressure, but to feel smothered by a man who always seemed two moves ahead.

The Psychology of a Master

Duran wasn’t just physical. He was psychological. His approach got in Leonard’s head in their first fight. He taunted, he pressed, he even spoke to Leonard during exchanges. He made the slick boxer abandon his blueprint.

For Leonard, the result was catastrophic. He didn’t just lose the fight—he lost control. And for a boxer used to dictating the rhythm, that was devastating.

What Duran taught the world that night was that boxing IQ isn’t limited to the back foot. It can live inside aggression, in body punches, in feints, and in bullying tactics that aren’t random but designed to break rhythm and will.

Why Duran Still Matters

Forty-five years later, fighters still look to emulate Roberto Duran. They study the tapes, mimic the movements, try to copy the attitude. But the truth is, very few have come close.

Why?

Because it’s incredibly hard to do what Duran did. Anyone can charge forward. Very few can do it intelligently. It requires perfect foot positioning, a sixth sense for timing, and the courage to stand in range while making subtle defensive movements. And beyond the physical, it requires mental dominance. Duran never let his opponents feel comfortable, even for a second.

He turned pressure fighting into an art form. Not the kind that paints clean lines, but the kind that sculpts masterpieces out of granite.

More Than a Legend—A Standard

Duran didn’t just beat Leonard. He beat the perception that matador-style boxing was inherently more sophisticated. He proved that aggression could be smart, even elegant. And he did it with a ferocity that never dulled the underlying brilliance of what he was doing.

Since his retirement, many fighters have been labeled as the “next Duran,” but almost all fall short. Some have the aggression, others the toughness. But the combination of brutality and brain that Duran brought into the ring remains rare—perhaps even extinct.

That’s because boxing, like society, often celebrates the clean and the pretty over the gritty and the complex. The matador gets the applause. The bull, even when victorious, is viewed as crude.

But Roberto Duran was no ordinary bull. He was a matador in disguise—one who didn’t wave a cape but came for you directly, without pretense, and left you wondering how someone so relentless could also be so refined.

A Legacy Set in Stone

Duran’s name still echoes across generations of boxing fans. Not just for his 72 wins before he faced Leonard. Not just for the way he fought in Montreal. But because he made people rethink what greatness looks like.

It’s not always about who lands the cleanest punch or who avoids the most damage. Sometimes, greatness is about who controls the chaos. And in Roberto Duran’s hands, chaos was a brush. The ring, his canvas.

Source: The Beltline: Roberto Duran made brawling both artful and beautiful

In the End, Beauty Is Where You Find It

Some fighters paint with elegance. Others sculpt with force. Duran did both. He carved out victories in tight spaces, danced under fire, and proved that a brawler could be as brilliant—if not more so—than the most technically gifted boxer.

So next time someone says a fighter is “just” a brawler, remember Duran. Remember Montreal. And remember that sometimes, the bull doesn’t just survive.

Sometimes, the bull wins.

Read More: A Show of Silence: Canelo and Crawford Let Their Actions Speak Ahead of Epic Showdown